Economic evaluation and value for money

Increasingly, the question of ‘value for money’ (VfM) comes up when evaluating policies and programs. A number of terms in common use, such as VfM, ‘cost-effectiveness’ and ‘return on investment’, are mistakenly used as if they all mean the same thing. Here’s a quick summary of terms to clarify and demystify the terminology.

Economic methods of evaluation compare the costs and consequences of an intervention with an alternative use of the same resources. All of the methods value costs in monetary units (dollars, pounds or any currency you choose). All of the methods adjust the value of costs and consequences according to their timing (a process called discounted cashflow analysis). They differ in the way they measure consequences.

The main economic methods of evaluation are cost-effectiveness, cost-utility, and cost-benefit analysis. For a quick illustration of these methods, see this infographic by Sara Vaca.

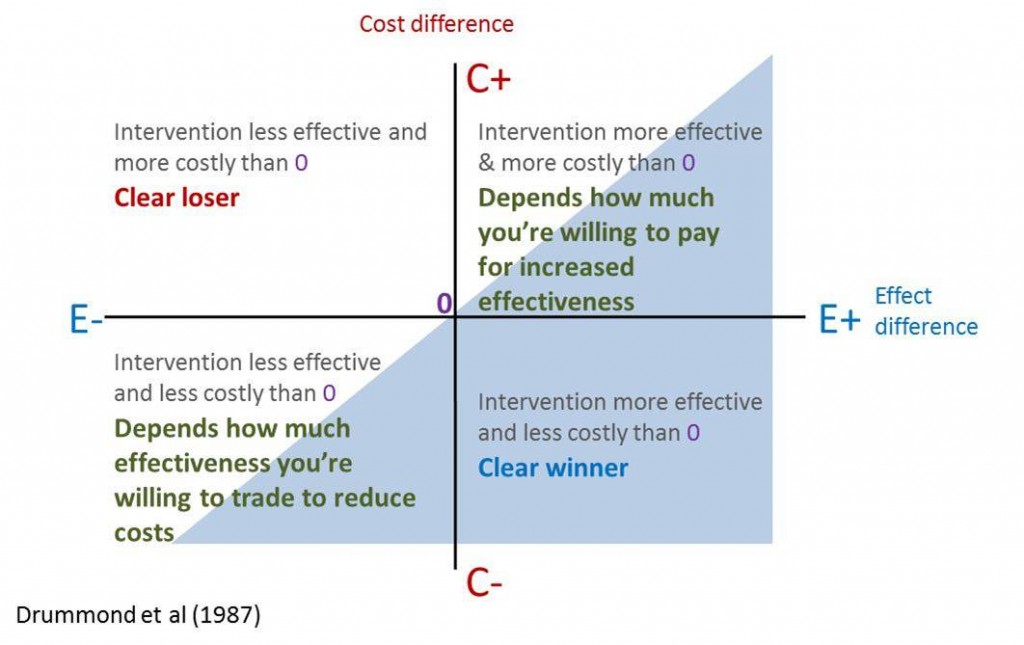

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) measures consequences in natural or physical units. Results are expressed in a cost-effectiveness ratio such as ‘average cost per life saved’. Ideally CEA is comparative, providing an ‘incremental cost-effectiveness ratio’ – the additional cost of an intervention compared to its next-best alternative, divided by the additional effects it delivers. Great when an outcome can be narrowly defined, not so great if the intended outcomes are broad and multi-faceted.

Cost-utility analysis (CUA) introduces an extra dimension to the consequences side of the equation – the human value of the effect. Empirically derived measures such as quality-adjusted life years (QALY) scale the ‘raw’ measurement of extended lifespans to take into account the quality of those additional years. Results are expressed in a cost-utility ratio such as ‘average cost per QALY gained’. CUA provides important insights into the value people attribute to different outcomes.

CEA and CUA tell us about relative value for money by comparing alternative interventions – but they can’t tell us whether an intervention is ‘worth it’ in absolute terms. So while they reveal something important, they don’t go all the way to answering the VfM question. Decision makers still need to judge whether, for example, a cost-utility ratio of $100,000 per additional QALY is worth paying for.

Cost-benefit analysis (CBA) and Social Return on Investment (SROI) measure both costs and consequences in monetary units. This means costs and consequences can be reconciled into a single indicator, such as net present value (essentially, benefits minus costs) or benefit cost ratio (benefits divided by costs). A net present value greater than zero, or benefit cost ratio greater than one, indicates that a program is worth doing on the basis that its benefits exceed its costs, and that it outperforms a reasonable alternative use of the same resources.

CBA is the most comprehensive of economic methods, because in principle, anything can be valued monetarily. Some costs and benefits have an actual monetary value (e.g., the money used to pay for the program). Some costs and benefits are bought and sold in markets (e.g., market wage data can be used to estimate the value of employment outcomes). If real markets don’t exist (e.g., what’s the value of increased self-esteem or hope?) we can set up experiments using pretend markets to find out what people are willing to pay for things.

All of these methods – CEA, CUA, CBA and SROI – help us to understand the efficiency of an intervention in different ways. They can help us to determine whether a program creates more value than it consumes.

Value for money (VfM) is a broader construct than efficiency. It is an evaluative question about how well resources are used, and whether a resource use is justified. Something might be worth investing in for efficiency and/or other reasons (e.g., social or distributive justice). Economic methods of evaluation can help answer a question about value for money, but often they are not enough on their own.

Economic evaluation is often used separately from other forms of evaluation. We think program evaluators should make more use of economic evaluation – and that economists should become more conversant in explicit evaluative reasoning and mixed methods approaches to evaluation. Systematically and transparently combining the insights from economic evaluation with those of other evaluation methods will strengthen our ability to assess VfM in social policies and programs.

Suggested reading on economic evaluation:

March 2019 / updated May 2020