Value for Money criteria

Value for money (VfM) is an evaluative question about how well resources are used and whether a resource use is justified (King, 2017). To answer an evaluative question we need a system for transparently and logically making judgements from evidence. This is called evaluative reasoning. One way to do this is by defining criteria (aspects of VfM) and standards (levels of VfM). Criteria and standards help us to:

- Identify what evidence we need to gather

- Organise the evidence and analyse it in a logical way

- Interpret the results on an agreed basis

- Make robust judgements

- Tell a clear and accurate performance story (King, McKegg, Oakden, & Wehipeihana, 2013).

But what are our VfM criteria? Criteria are determined on the basis of values – “principles, attributes or qualities held to be intrinsically good, desirable, important, and of general worth” (Stufflebeam, 2001). These values will vary according to context. For example:

- One policy might have an objective of improving access to basic health care for an under-served group – reflecting values of equity and human rights.

- Another policy might aim to preserve indigenous language and culture by providing pre-school immersion programs – reflecting values of cultural sustainability.

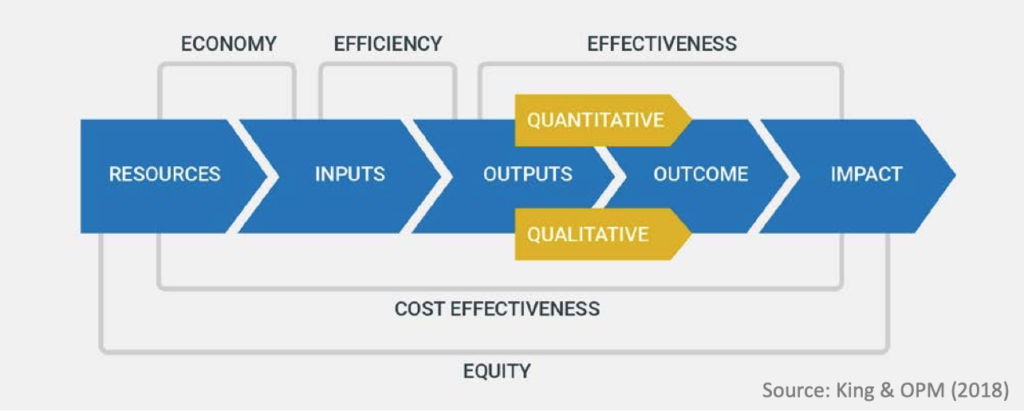

A common set of VfM criteria, the “Five Es” are used by the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) of the UK Government and other organisations to assess VfM in aid and development programs (DFID, 2011). The Five Es are not the last word on VfM criteria but they do offer a reasonable starting point (King & OPM, 2018).

FCDO’s criteria of economy, efficiency, effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and equity are valid criteria of VfM. But they are not the only criteria. Sitting behind FCDO’s criteria are a more generalisable set of principles that can be applied more flexibly to respond to different contexts.

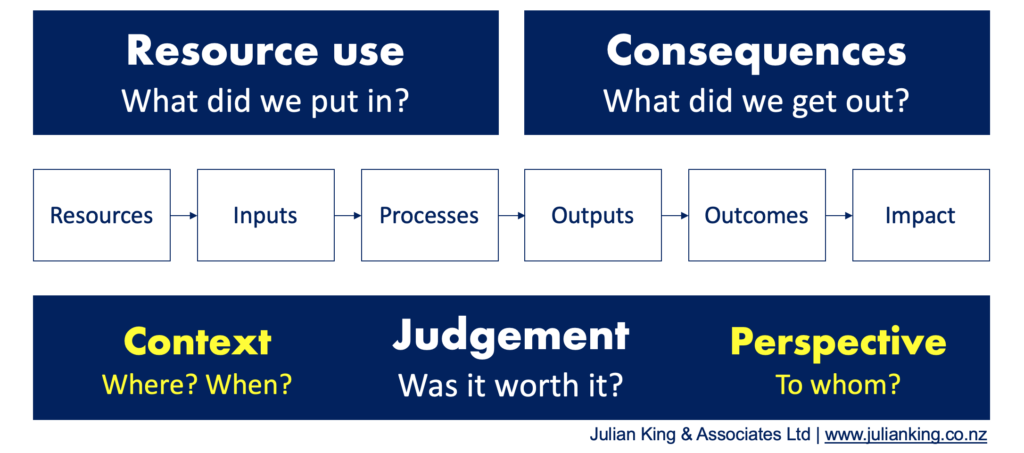

Broadly, a VfM question can be broken into three parts:

- Resource use (what did we put in?)

- Consequences of the resource use (what did we get out?)

- A judgement (was it worth it?)

These parts of the VfM question correspond to different sections of a theory of change – just as FCDO’s criteria do.

Real programs are seldom as linear and sequential as this stylised results chain; nonetheless it’s a useful simplification for organising VfM criteria. We can add complexities as required. For example, somewhere in between program processes and outcomes, participants may be deciding whether to engage with the program, based on their own assessments of what they’re putting in, what they’re getting out, and whether it’s worth it to them (thanks Kate McKegg for this example).

FCDO’s Five Es cover all three parts of the VfM question (what did we put in, what did we get out, was it worth it?), but they don’t represent all of the possible dimensions of VfM. Some additional examples of VfM criteria are outlined below.

The first part of the VfM question (what did we put in?) covers the use of resources and inputs to do something. It includes FCDO’s criterion of ‘economy’, which focuses on sound procurement: Are we or our agents buying inputs of the appropriate quality at the right price? (Inputs include things such as staff, consultants, raw materials and capital that are used to produce outputs) (DFID, 2011, p. 4).

Good procurement is relevant to good resource use. But there are additional things we might want to understand, such as:

- What sorts of resources were invested. Opportunity costs come in different forms and are not limited to the value of donor funds (e.g., by facilitating program access to a community, local leaders might invest and risk their relationships and reputations)

- Relevance of the resource use (e.g. relevance to the needs of beneficiaries and to the strategic priorities of the impact investor)

- Affordability (e.g., can the intended program be delivered, within available resources, to sufficient extent to achieve its objectives?)

- Riskiness of the resource use (e.g., is the program within appropriate boundaries of risk tolerance for the context?)

- Ethical resource use (e.g., using resources for their intended purpose and ensuring no harm is caused)

- Cultural fit (e.g., congruence with service users’ values) (Goodwin, Sauni & Were, 2015)

- Fitness for purpose (e.g., is the program design appropriate to its aims and context?)

- Fidelity (e.g., is program implemented in accordance with an agreed design or set of principles?)

The second part of the VfM question (what did we get out?) covers everything that happens as a result of the resource use – from the very first deliverable to the long-term impacts, intended and unintended. This includes FCDO’s criteria of efficiency and effectiveness, among other things.

FCDO’s definition of efficiency is focused on one aspect of productivity, sometimes labelled technical efficiency: How well do we or our agents convert inputs into outputs? (DFID, 2011, p. 4). In complex programs and policies, it can be useful to consider three dimensions of productivity:

- Technical efficiency (doing things right) – maximizing delivery of outputs within a given level of resources or inputs

- Allocative efficiency (doing the right things) – the right mix of inputs and activities to meet needs or strategic objectives

- Dynamic efficiency (improving technical and allocative efficiency over time) (NZ Productivity Commission, 2017) – e.g., through adaptive management, innovation and learning.

I would add an extra dimension to the list above, though I’m not aware of economists having a name for it. I call it relational efficiency. Relationships, communication and trust are the glue that enables programs to work efficiently. Without this glue, resources are squandered.

FCDO’s definition of effectiveness is focused on outcomes: How well are the outputs from an intervention achieving the desired outcome on poverty reduction? (Note that in contrast to outputs, we or our agents do not exercise direct control over outcomes) (DFID, 2011, p. 4). Poverty reduction is, of course, one example of an outcome. More generally we might want to consider:

- What changed? (including intended and unintended changes)

- In what ways? (the nature of the changes)

- To what extent? (enough to make a meaningful difference?)

- For whom? (and what is their perspective on the changes – for example, how does their lived experience compare to independent measures of change?)

- In what circumstances? (are certain contexts or mechanisms important to achieve particular outcomes?)

- Attribution or contribution (how do we know the program caused or contributed to the changes?)

The third part (was it worth it?) is the crux of the VfM question. It requires a basis for reconciling the resource use and its consequences, to determine whether the resource use is justified. Determining whether an investment is ‘worth it’ is a matter of context (where and when) and perspective (to whom). It demands an evaluative judgement based on evidence and logical argument.

FCDO’s VfM criteria recognise that there may be trade-offs between maximizing the impact of each pound spent (cost-effectiveness) and reaching the poorest (equity).

FCDO’s definition of cost-effectiveness reflects a general concept of maximising outcomes within a given level of inputs: How much impact on poverty reduction does an intervention achieve relative to the inputs that we or our agents invest in it? (DFID, 2011, p. 4). In economic evaluation, ‘cost-effectiveness’ denotes a particular method of analysis. FCDO’s definition, however, doesn’t require the use of this method. It simply requires a judgement about whether sufficient impact was achieved for the resources invested.

The inclusion of equity in FCDO’s framework sets an explicit expectation that VfM should not be judged solely on the basis of cost-effectiveness. Reaching the most disadvantaged may be more costly. When we make judgements on the effectiveness of an intervention, we need to consider issues of equity. This includes making sure our development results are targeted at the poorest and include sufficient targeting of women and girls. (DFID, 2011, p. 3).

Cost-effectiveness and equity are two important criteria of VfM – but there are more. A policy or program may be ‘worth it’ on the basis of various considerations, which include:

- Sustainability (e.g., environmental, social, cultural, etc.)

- Ethical bottom-lines (e.g., providing an entitlement, upholding a treaty, or protecting a human right)

- Cultural or historical value (e.g., the significance of something to the heritage, identity, or wellbeing of a cultural group)

- Scientific value (e.g., learning what works and what doesn’t work)

- Equity, human dignity, fairness, and distributive impacts (Executive Order No. 13563, 2011, p. 3821)

- Outcome-efficiency as estimated using economic methods of evaluation.

This is not an exhaustive list of VfM criteria. However, the three questions of what did we put in, what did we get out, and was it worth it, provide a useful framework for scoping contextually appropriate VfM criteria. The Five Es cover these three questions and provide a reasonable starting point, but do not cover all possibilities.

Identifying VfM criteria is just one of the steps involved in designing a VfM framework. The next step is to set standards: to what extent (and in what balance or mix) must these criteria be met to represent adequate, good, or excellent VfM for the resources invested? (King & OPM, 2018). As the investment increases, so should expectations.

References:

Department for International Development (DFID) (2011). DFID’s approach to value for money.

Goodwin, D., Sauni, P., Were, L. (2015). Cultural fit: an important criterion for effective interventions and evaluation work. Evaluation Matters—He Take Tō Te Aromatawai, 1, 25-46.

King, J., McKegg, K., Oakden, J., Wehipeihana, N. (2013). Rubrics: A method for surfacing values and improving the credibility of evaluation. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 9(21), 11-20.

King, J. (2017). Using Economic Methods Evaluatively. American Journal of Evaluation, 38(1), 101–113.

King, J. & OPM (2018). OPM’s approach to assessing value for money – a guide. Oxford: Oxford Policy Management Ltd.

NZ Productivity Commission (2017). Measuring and improving state sector productivity.

Stufflebeam, D. (2001). Evaluation Values and Criteria Checklist.

April, 2019